Essays

Connecitivity

Moving, drawing, animating

The animation, Connectivity, was made with drawings and words composed by four artists who have not been to Antarctica. I was interested to find out how other people imagined Antarctica, and if I could animate some connection between their imaginings and my remembered sense of it. Improvising with gestures, drawings and words were ways to engage in dialogue with other people to see what thoughts and feelings might arise. I wanted to know how an animation could be made to reflect some understandings that might arise from our dialogue. I wanted to make an animation that would capture some of the interactions that might occur between people engaging with Antarctica, through imagination and memory.

Artists Christine McMillan, John Smith, Kim Holten and Yoris Everearts had agreed to participate in these explorations. Each had expressed an interest in Antarctica, so I assumed they all knew something about it. When we met, in a cold basement room with a hard concrete floor, Yoris immediately remarked how it was like being in Antarctica. All agreed, laughing. So we know Antarctica is cold and hard. What else? We sat in a circle and I gave everyone a soft lead pencil, some sheets of white paper and small board to lean the paper on. I asked them to put down the words or images that came immediately to mind when they thought about Antarctica. I asked them to do this quickly, without talking with each other or looking at each other's work. This seemed to be difficult for some, as I watched them gaze off into the distance for a while before putting pencil to paper. Others began straight away. The words that emerged within three minutes were:

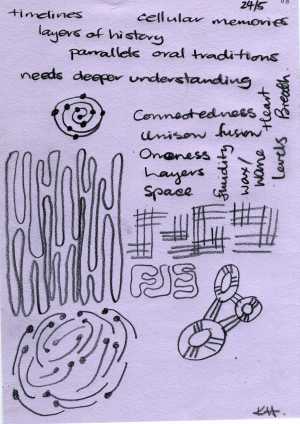

space, hostile, beauty, relationships, melting, lacking man made cul- ture [Christine]; collage of impressions entirely through the media and 2nd or 3rd hand, desolation, strange feelings that arise when you are out of the mainstream [John]; timeless cellular memories, layers of history, parallels oral traditions, needs deeper understand- ing [Kim]; frozen memory, body, matter, purity - white [Yoris].

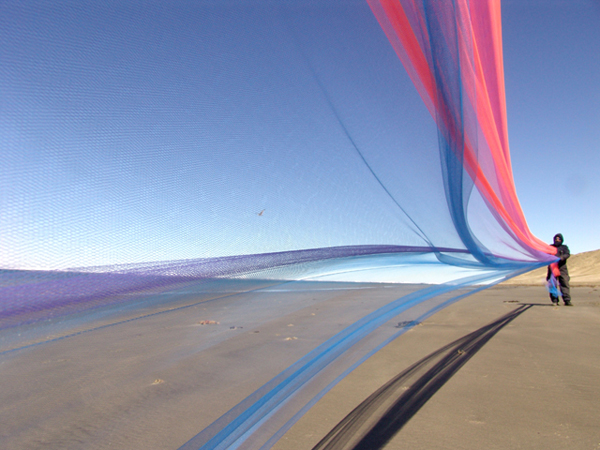

I recognised in all these words the Antarctica I had experienced. Specially interesting was John's 'collage of impressions entirely through the media and 2nd or 3rd hand'. So much of what I know about Antarctica comes to me that way. Antarctica is huge, and even if you have been there, you depend on the media to get an idea of its other landscapes you will most likely never visit. Or you can listen to what people will tell you about places they have known there. The Antarctic Peninsular, for example, is more in the media than East Antarctica,where I went. Australian expeditioners often call this West end the 'pretty end', in contrast to our more austere East 'working end.' Extending further north into warmer latitudes, the Antarctic peninsular contains more wildlife, and more rock protrudes through its melting ice. It is more colourful and alive in its physical expression of global warming. From the picture post card photos it looks beautiful and fragile. Satellite photos taken in recent years reveal to the world the dramatic collapse of the great Larson Ice Shelf. Methane escaping from other parts of the peninsular through rapidly melting ice is a phenomenon I can most clearly grasp through an artist's visual response. Images of Andrea Juan's Antarctic installation, Methane can be seen on the artist's website. They dramatise the human impact on our planet's fragile atmosphere, with swathes of floating coloured tulle representing toxic chemicals leaching from the ice. When I first saw this image I was moved to learn more about the science that inspired her work. I found the transcript of a conversation she had with the scientist, Rudolfo del Valle, as they traveled towards Antarctica. He explained to her that:

Through the increase of the greenhouse gas affect, we are causing the temperature to rise too much and just in the middle of a rising cycle - this might break the cycle. I believe this additive interference is already dangerous. Nature might be unable to restore the balance.

This is the kind of dialogue an artist can have with a scientist that can shape her response to Antarctica. Her response will also be shaped by how she is predisposed, and the sort of materials and methods she has available to her.

Fig.01 Andrea Juan, Methane. Antarctic performance, Jubany, Argentine Antarctica 2005.

In the cold basement room in Sydney I was in dialogue with four other artists about Antarctica. In all the words they wrote I recognised much of my own experience. Fore example, many expressed what the landscape lacks. Christine wrote that Antarctica is 'lacking man made culture.' By 'culture' she meant a long period of human history that shapes a place. Her word 'space' suggests to me a lack of features we can see, features that we would expect to find in more familiar landscapes. I read this as meaning the external physical landscapes one can know, the physical places you can walk through, as well as the internal landscapes that are shaped within our selves through feeling responses to our external world. The word 'hostile' suggests an extreme lack of emotional warmth, and even anger, expressing itself in the landscape against humans. Some people grouped words in ways that suggest some contradictory feelings. I can read Christine's words 'melting' and 'relationships', for example, to mean the opposite of her words 'hostile' and 'lacking man made culture.' 'Warmth' could reflect the intensely tender human connections that people can make with each other living in close proximity to each other in a dangerous place, and 'melting' could mean an emotional surrendering or release. I recognised my own sense of Antarctica in their responses - a strange mixture of fear and desire.

Kim and Yoris wrote that Antarctica has 'memories' that are 'cellular' and 'frozen'. Their words suggest that Antarctica is a sentient, feeling organism, where the ice knows its own past and 'needs deeper understanding'. Their words accord with the Gaia theory of the Earth as a living being, the theory also reflected in the words of Antarctic scientist, Bill Burch:

...it's the ancient air bubbles trapped in the ice which allow us to chart Gaia's atmosphere going back millions of years.

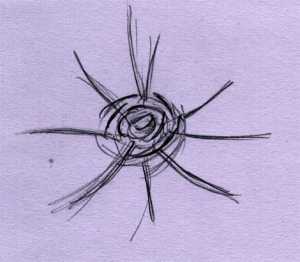

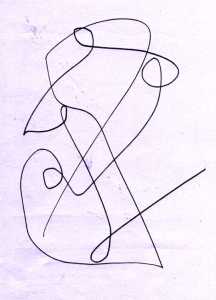

Some of the artists drew images alongside their words. Some wrote their words as pictures. These offered visual clues about how they knew Antarctica. Christine's words and symbols reveal a layering of lines, ehoing Kim's phrase, 'layers of history.' Both were drawing on responses to an imagined place, and in their different ways arrived at a similar sense of it. I was interested and surprised to find such strong correlations between the responses of two people who had never met each other before. And I had not worked with Kim before this session. Christine said she drew the words as images, to reflect their meanings. The 's' of 'space', for instance, suggests depth beyond the page. She said she was mindful of the use of capital and lower case letters, and the different force each can have. The capital 'H', for example, gives an edge to the meaning of the word 'hostile'.

Fig.02-03 Christine McMillan 2008

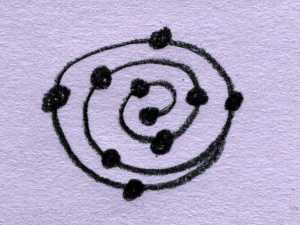

Kim drew a coil, which she described as representing things connecting. This in turn echoed Christine's word, 'relationships', which she explained as the relationships you would have with people in Antarctica that might be very challenging in such a confined environment. She said it also represented the relationship you would have with the buildings and the land around you. Her star-shaped form represented, she said, being connected with everything beyond Antarctica - how Antarctica is inked to us.

Fig.04 Kim Holten 2008

After hearing each response to imagining Antarctica, we moved through the space to a polar soundscape composed by Max Eastley, of a ship moving through ice. We moved as a group to raise awareness of our bodies, the space we were in, and the other people sharing that space. With eyes closed we stood still, and then gradually explored ways we could feel our weight through the floor We pushed our weight down through bended knees, and imagined, rising from that bend, the top of our head reaching high above us. And then, with eyes opening, we played with feeling through our arms and torso the line of the horizon, extending our gaze outwards into the room. We moved towards and away from the limits of the room, and each other. We played with straight and curving floor patterns. The score for this movement improvisation, was near and far, curved and straight.

A movement score is a set of limits imposed for performing an improvisation. Within such limits, variations in the use of space, time and energy and explored. A score provides a neutral structure within which dancers can attach their own meanings. Meanings can express themselves in different ways, such as a narrative,feeling state, or purely abstract play. No emotional state is prescribed. This way of working has its origins in the work of movement analysts Rudolph Laban, which in Australia has continued through the work of such artists as Joanna Exiner and Al Wunder. Laban's approach to improvisation has been integrated into a range of arts practices including theatrical performance, performance art and arts therapy.

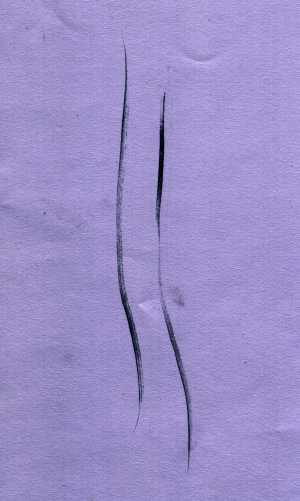

After the movement improvisation, everyone was invited to draw from that experience, to transfer how they had moved into lines on paper. Unlike the initial drawing task, this time no hesitation observed, no premeditation about what to draw. The drawings appeared to come more easily after moving. Most made several drawings, in rapid succession, on many sheets of paper. Christine said she enjoyed exploring the variations in pressure she found possible when using soft pencil. This reflected, she said, how she felt her whole body weight through her feet into the floor. She said that when drawing this she had remembered another session we had weeks earlier, when I had suggested exploring that idea, of feeling one's weight through the soles of the feet. She also said she was wanting to draw differently than she had in the first exersise. She wanted to break away from those patterns, to explore other possibilities. This suggests that the improvised moving may have influenced Christine's approached to this drawing.

Improvising to a score encourages exploration of different ways of doing the simplest things. It provides a kind of lense through which the moving body can draw itself through time and space. It encourages shifting from habitual ways of moving, with more spontaneous, unpremeditated responses to a place. Christine said the lines she drew recalled an earlier line quality that she made to reflect the feel of ice. But t in this instance they also reflected her awareness of the immediate physical space. There were open slots in the ceiling through into the room above, where some renovation work was happening. It was a most surprising and unexpected visual intrusion. These long slots of light above caught her eye and influenced her moving. This in turn became embodied in her drawn lines. Such unexpected connections can happen easily in the moment of improvising, where immediate sensory awareness can be embodied in a dance and joined with other past memories. The sensitivity rendered lines and modulations of tone convey to me a sense of careful deliberation in her sensory response. The lines have a controlled delicacy that describing the this striking aspect of the room's architecture.

Fig.05 Christine McMillan

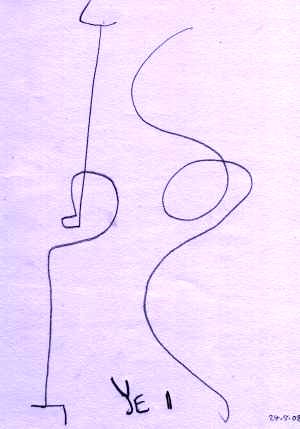

John described his drawing as representing the curved and straight pathways he moved along the floor. Having watched him move, I recognised the lines, shifting between long and short, and the smaller looping turns he made when changing direction. John had used various body parts to lead himself through space. His drawing overall resembled a shematic figure, some ancient totem.

Fig.06 John Smith

Yoris made several drawings on several sheets of paper. His lines revealed the discrete structured gestures of his dance. I had observed pauses between his gestures, which were suggested in his drawing of lines as separate elements, with each line showing a clear start and an end point. His lines appeared sculpted, or constructed, and I imagined them, like John's lines, to form totems.

Fig.07 Yoris Everaerts

Working on just one sheet of paper, Kim made her drawing after moving in a space on the page beneath her initial words and symbols. She added more words that reflected her movement experience: connectedness, unison, fusion, oneness, layers, space, wax/wane, levels, heart, breath. The drawings she made reflect her physical explorations around the room: moving through straight and curving pathways along the floor, and mov- ing her whole body upwards and downwards. There seems a sense, in the bottom left hand side of her drawing, of her awareness of the spaces between herself and others. Then in the bottom right, a more physical connection that she made with others is reflected. Kim had not done this kind of work before and expressed excitement about the experience and the words and drawings that emerged from it. Her drawings were varied, reflecting the different ways she had interpreted the movement score.

Fig.08 Kim Holten

When composing the animation, Connectivity, I improvised, working from a position of not knowing what the final outcome would be, and composing in the same spirit in which the words and drawings that I was using had been composed. I approached making the animation as I would an improvised dance. It would be a discrete gestural response to some dialogues that happened between a group of people about Antarctica.

Composing an animation through improvisation is a slow process. I have found it important to work as quickly as possible in the initial construction, when working out its direction. I have found it useful not to question ideas that come immediately to mind, and to stick one that suggests itself as important. Ideas emerge through placement of elements in space and time. Elements are images, text, sounds and gestures. Just as dancers position themselves in a space, so placement of elements sets up dialogues between them. Ironically, hours can be involved in tweaking timing and positioning, to convey the freshness of connections that present themselves.

Words and images that seemed to connect were animated to simulate how they were composed. Tracing marks each artist had made with varying timing evoked the gestural quality involved in writing and drawing. The animated marks suggest the varying rhythms involved in the act of moving pencil on paper. Tracing the marks as closely as possible to those of the originals, I became aware of the different gestural qualities of my own mark making. This was an interesting and unexpected aspect of working with other people's material. It was kinesthetic evidence of how differently we gesture, in drawing as well as in dance. Tracing other people's marks, I felt the shift away from habitual kinesthetic patterns.

Unexected readings of the animated marks suggested themselves readily. The totemic quality previously observed in John's drawing became accentuated by overlaying a mirrored version of itself, to became a symmetrical form. Moving John's words, 'strange feelings', downwards below this totem form, suggested a new meaning for thm The words now suggested there were feelings beneath a level of conscious knowing. This I see now reflects my own position, of starting the exploration from a place of not knowing if and how connections would emerge. The image of the totem fades away, only to return again to be re-read with Kim's words, 'cellular memories.' I was interested to see how the meaning of the totem might change. Now I could read it as a sentient being, comprised of cells that could each remember. Kims words had suggested a new reading of John's image. Having drawn John's original shape over itself in reverse had created a whole network of internal shapes that suggested a cellular structure. Visually, and through attaching the new word to the image, new connections were drawn that were not visible before. The totem, then could mean different things, depending on its relationship with surrounding elements, and how they were positioned and moved. The sense of the totem as a physical form with an internal cellular structure was just fleetingly suggested. A sense of its material physicality was slowly then subverted by moving the whole form through space. It was like moving the drawing off the page it had been drwan on. In this way, the totem remains two dimensional, representing an idea that is free to find its own connections. The way the totem angles through the space and fades away is mirrored by the gesture of an incoming cellular form, drawn by Kim. The two forms seems to move with an awareness of each other, as if dancing to the same rhythm. Then the cellular form falls downwards, as if to join the earlier 'strage feeling' as an unconscious memory beneath. Layered over this are the animated lines drawn by Christine, leading the eye still further down. Layers of different people's personal memories and ideas are drawn down together into some unseen place. Animating the words 'connectedness', followed by 'relationships' suggests that even though these layers are invisible, they are connected. The more discrete, sculptural forms of Yoris then draw themselves in, with the coiling extension of one form then connecting with Kim's coiled 'connecting' form.

The following section is a small gesturing dance between Kim's cellular form, and Yoris's sculptural forms, and his last word, 'matter.' As 'matter' descends, the idea is suggested of our material destiny. Depositing our cellular forms as sediments, we may one day be compressed, form coal, and power some future human forms.

The ending suggested itself through Kim's word, 'breath', that led to bringing her connecting coil upwards with that word. The rising 'breath' meaphorically connects all living things, sharing the wworlds one atmosphere.

Connectivity took took three days to make. The sound, by Max Eastley, was added last, reconnecting the dialogues between words and drawings with their origins in a dance to that music.

What was the value of this work? A dialogue occurred between some artists reflecting on Antarctica. The completed animation reflects something of the tenderness and delicacy of interactions I observed happening between the participants and Antarctica as they imagined it. It reflects, too, a certain tentativeness we seemed to share about entering into unknown territory, embarking on an experiment in a space new to all of us. Then through a gradual unfolding of ideas connecting, a resolution was symbolosed through 'breath', and a shift in feeling came through a change in direction, uplifting. Working with these artists demonstrated that moving can help release a flow of thoughts and feelings about Antarctica. Working on the animation validated the process as a way to connect people with Antarctica. It also helped me to identify my own voice. Working only with other people's images and words made it easy to see what was mine: the choreography of lines, and timing, the spatial design and sequencing. But most signifcantly, the passage of thought from tentative to resolution. There was great personal value for me, then, in this way of working. Like dancing, it helped release flow of thoughts and feelings. There was value also for the participants. The improvisation process, and the final animation reflecting that, offer glimpses into some thoughts and feelings that were shared. Participants can contemplate and follow up with their own inquiries. They may further question, for example, what 'frozen' and 'cellular' memories mean to them.

Weeks after this workshop, Kim said she had been moved by this experience in her own arts practice, to further her idea of cellular memories, and what it means in terms of identity. As an arts therapist and sculptor, Yoris Everaerts said there was value in this kind of work for releasing feelings, and opening up possibilities for their creative expression. The value of the animation for an observer is that it reveals some connections identified between some people sharing thoughts and feelings about Antarctica. This invites observers to consider what that measn to them. As an animated dialogue, Connectivity has the potential to connect others with Antarctica by suggesting other positions from which to consider Antarctica and what it reveals about our impact on the planet.

Sydney, August 2008