Appendix

Interviews

Foundation work Interviews Science notes for Energies Working drawings and photos

FRED ELLIOTT and JACK WARD JACK WARD JO WHITTAKER PAMEN PEREIRA DOMINIC HODGSON SIOBHAN DAVIES STEVE NICOL

Melbourne, March 2007

(Left) Author with Jack Ward, Radio operator, Macquarie Island:1950, Mawson: 1955. (Right) Author with Fred Elliott, Meterologist, Heard Island:1953, Mawson: 1953, 1955, 1958

I met Jack Ward at an exhibition of Sydney Nolan's Antarctic paintings (Nolan in James, 2007). I had observe him study, with unusual intensity, the brush marks in a corner of a picture. His whole body stooped forwards, as if to more fully enter the scene. I asked if he was an expeditioner. 'How did you know that?' he asked? I didn't really know what to say. His blue eyes had an intensity I had seen before in people who have worked in Antarctica. His whole body had seemed totally engaged with a picture of it. Jack said he had worked as a radio operator in Antarctica in the 1950's.

After some discussion about paintings, and about my interest in his experience, Jack agreed to a recorded interview. He said I should talk to his friend Fred Elliott, an artist and fellow 'winterer'.

Fred

I can make myself at home almost anywhere I go I think (gazing sideways to his left, remembering perhaps). This is probably because I went off to boarding school (pause)...I'd just turned eleven and had seven years there, so you learn to sort of go with the flow, or keep your head down (laughs), or whatever. And then I was in boarding houses and so on when I was training to be a teacher ...(softly) trying to be a teacher.

Jack

(to Fred, mocking) Trying to be a teacher... (to me) He's good, very good.

Fred

I was also fortunate having a father who was very keen on being in the country, took a keen interest in it. He was all over Victoria as a young man (arms stretching out). When John Bechervaise came back from overseas to the school I was at (Geelong College) he started up the hiking, and I was right in on that. I started off with John Bechervaise as a student, although he never taught me.

I was just so used to being where there were no tracks, that I found it perfectly natural to be in such places. It's been like that as long as I can remember. I think that Antarctic landscape is more apparent; easier to understand than a lot of Australian landscapes. Sure, Nullarbor is an exception, where the sky comes down to your bootstraps (as they say) and, like the Antarctic plateau, you are never too sure whether it is hollow or not under your boots.

Jack

It's strange.

Fred

I was also thinking, as I was coming to see you, about the night we camped on the top of Mount Woodroffe. With just another young man (a white man), and three young Pitjantjatjara men (from the Musgrave Ranges). And the whole of Central Australia seemed to be laid out before us, with a brilliant sort of sky, and the boys singing corroboree songs and so forth in their high pitched voices. And that was just to say, well, you know, that's right.

But in Australia a lot of Australia is sort of more clothed with vegetation, You can't really see the bare things. But in the Antarctic it's sort of all laid bare and sort of all run by physics. Almost.

Jack

What do you mean, "all laid bare"?.

Fred

There's nothing hiding the ice. The rock is bare and the ice is flowing round the rock and cracking and shutting up again and boulders fall down onto the ice and they stream away down from the mountains and you get little streams, although the temperature's below freezing, the rock warms up in 24 hours of sunlight and melts the snow and ice alongside and it goes running across (this is in summer time) and the wind that blows out from the high pressure area, originally it would come up from the equatorial regions and would flow up with the great thermal, pull of the sun and then flowed back down and to the Pole and then come out again. Flowed out again. And you got that coming and going. And the ice underneath flowing out. And on top of that you've got the wind where the air gets very cold and gets into valleys, just like water it rolls down. That's your catabatic in fact.

And then In winter time, the sea ice is stretching out in an area as big as the Antarctic itself, and it's all hinged and the huge power of the tide which is the pull of the moon on the earth taking it up and down and you can hear if you're out by yourself on a still night the creaking of the ice of the tide crack as it goes up and down.

This is what I mean by "It's all laid bare"

Lisa

You mentioned physics.

Fred

Well it is physics. Yes. But it's nature, natural physics.

Lisa

You described it with a mixture of the artist and the meteorologist.

Fred

(laugh) Yes, we shouldn't need to differentiate. Wilson, he was a good artist. I was just looking at his books again.

I love the place. Heard Island I think I like even more. It was grand. It really was in those days. The glaciers now have lost a lot of ice and snow. But rotten weather.

Jack

Well I have a feeling that the immensity of the continent dampens your emotional aethetic responses to the scenery. It is just so bloody huge, so extensive, and also, if you happen to be out any distance from the base (50 miles) then at night then the immensity of it comes to you not so much visually but in the sense of the stillness, the cold, and the caprice of the wind which will suddenly, from nothing, come up with a (soft, eerie) "hoooo", like, you know, a disembodied spirit of tremendous force and often that doesn't last long but I remember waking up several times to this palpitation of the wind which scared me stiff I must admit because it gives you a sense of what the wind can do which is almost unlimited.

But it was incredibly beautiful at evening when the sky of the setting sun took on unusual hues and at morning and watching the sunlight creep over the ice was really quite delicious.

But I believe (I don't now that Fred agrees with me) I believe that most people who went there were either intimidated by the place so that they didn't really look at it as a visual experience or, in the case of scientists, they had so much to do and I know this from a close friend who was a cosmic ray physicist, that their minds never came off their work. For instance on Macquarie Island we had quite an emotional upset in the camp which threatened to disrupt it deeply and this scientist (I let him see my diary on it) and he said "look, I just never noticed that. He was so busy with his cosmic ray work. And they were, they were terribly busy, and with the aurora work. And I think this applied to the vision of the place too.

We have a regular lunch meeting called (very unoriginally) the Chelsea Pensioners) once a month and I never hear any of them talking about the aesthetics, the delight of the place. And recently, like you, I went again to see the Nolans and I said to a small group, that I'd heard (the Chelsea Pensioners say) "Gooood, aren't they terrible. They're nothing like it! He wouldn't know how to paint it." And they were people, all of them except perhaps George, who had spent a year there. They were quite offended that he'd taken their concept away from them, or if not that, he hadn't realised how important was their concept. Well, yu know, I could only gasp at that. I don't know that the Nolans were a perfect representation of continent. I'm sure they weren't but they were extraordinarily at times powerful and interesting and imaginative. A few of them were not. But anyway that was their reaction. I was stunned by it.

Lisa

Were any of them scientists?

Jack

Mostly they were people like surveyors. In that group I don't recall there being a physical scientist. But I think that is the case with most of the scientists. John Bechervaise's books are the result of a highly intelligent man with an aesthetic background and a capacity to draw and paint and a great fondness for long big words (both laugh).

Fred

He went to the Courtauld Institute.

Jack

Yes, he studied with Anthony Blunt and (James) Byam Shaw

Lisa (to Fred)

And he was your teacher. But your language is succinct

Jack

Oh John was a 19C leftover actually. That's an unkind thing to say but to me, he represented his father and grandfather, who were rather powerful figures, specially his grandfather. And he was immersed in the flowery language of the period. But I don't mean to disparage him. He had many considerable talents and perception. But I do think, speaking from my experience that for instance I've never heard Bill Storer who did a lot of outside work, I never heard Lyn Macey talk of the beauty and variety...

Fred

Perhaps Dovers might have.

Jack

Dovers hight have. Indeed. His diary doesn't show it.

Fred

You'll have to read his book.

Jack

Did he write a book as well? Oh, I haven't read that.

Fred

Oh yes. It's Huskies. Called "Huskies".

Jack

That would put me off anyway.

Fred

But it's a very good book. It's about when he went down with the French and the station burned down and he stayed down with the party and transferred across to whatever it was the other station.

Jack (to me)

This was the first Officer In Charge (OIC) of a land base at Mawson, the establishment of it. And then he did a fairly major traverse attempting to get to the Prince Charles Mountains but the equipment was so hopeless then that he had to abandon his second attempt, though he got quite a way, as did John Bechervaise who had two attempts and the blooming weasles broke down, hopelessly, each time. And John would never have risked his teams lives, so perhaps he could have risked going further but he wouldn't. No. I respect that.

But I never heard any of them say anything ... be excited about the appearance...

Fred

A lot of people wouldn't say if they were...

Jack

Mmmm...

Fred

...Because it would be unmanly.

Jack

Oh, come off it.

Fred

No, no. It's right I reckon.

Lisa

Mmmm. I was going to ask about that. You two don't seem to have any inhibitions about waxing lyrical.

Jack

We're not very manly.

Fred

(laughing) We've got hairs on our chests haven't we Jack?

Jack

(laughing)I used to.

Fred

One of the things we have left out is the people in the Antarctic. To me, they are more important than the actual...than to everything else. You meet someone like Jack, and (laughs) you have to put up with them for twelve months.

Jack and Fred

(laugh together)

Melbourne, March 2007

Jack agreed to talk more about his Antarctic experience. I was particularly interested to hear about his sensory connection to that environment. Again, we met at his place.

14:30, 2007-03-19 North Melbourne

Lisa

You were telling me about your background, training...

Jack

When I left school, High school with matriculation, I got a job as a laboratory assistant and consequent on that I went to Melbourne Tech and did a 4-5 year Diploma of analytical chemistry, or Applied chemistry. ..and it had a very good physics course. It emphasized physics well, and the physics staff were very advanced. And we did a lot on the physics of sound and, ah, all of that, much of which I've forgotten, ah, and I s'pose that helped make me conscious of the nature of sound and the things which produce sound, the reverberations that develop ...in a way made me interested in the winds of the Antarctic, depending where they came from, they had different tones, and styles, short of the absolutely frightening crashing roar of the blizzards, but the, as I think Fred had explained, the cold wind at the top of the ice shelf in Antarctica, at night when the lower areas have lost the warming effect of the sun, that wind spills down the slopes into the lower regions and it's called a katabatic...it can be extremely harsh and strong.

Other times it's just preceded by a stirring, just a weak, the poetic word is cesurus (?), ah, and ah,which then can suddenly develop into a roar (emphasized), and then, suddenly subside, and may come again two or three times and totally disappear, or, develop into a flaming gale. I can't really talk about a 'flaming gale', but ah...um, that's just one, aspect.

The other thing, at night, on the ice shelf, you'd hear the strangest sounds: cracks and bangs, and these are just the movement of the ice over unevenness in the earth beneath so that you get a compression, and rarefaction, of the ice with constantly cracking noises, and then suddenly you'll get a bang (emphasized) ss perhaps a section moves away, or an ice cliff falls...and so it's not unbroken, the night.

rarefaction, a term used in applied physics to describe the spreading apart (as opposed to compression) of molecules in gasses such as air, caused by the passage of a sound wave.

Lisa

How often would would you hear a sound in the night, and would it be every night?

Jack

Oh, every night, every night, you'd hear something. It depends (soft laugh) how heavily you were sleeping I s'pose, yeah.

Lisa

So you'd need to be sleeping quite close to the ice.

Jack

Well you are. You're sleeping on, well usually ...well depends. You might be sleeping in one of the mechanized vehicles or alternately in a tent, which you sleep in on a couple of layers of insulation directly above the ice, directly on the ice.

Lisa

So when You were in Antarctica, what were the sleeping quarters on the bases like?

Jack

Oh, the sleeping quarters on the bases were quite, domestic. You know we all had a cubicle in a hut divided into about six cubicles.

Lisa

Were they called Dongers?

Jack

No they weren't in our day. They subsequently were. They were called huts. We were much more literal, and perhaps literate. And they were warmed by a briquette stove, which had to be watched on blizzard nights, in case the vent snowed up in which case you'd get carbon monoxide ...and that was a night watchman's job to check the stoves in all the huts. (Carbon monixide poisoning)... was common enough even in small levels in tents with Primus stoves because in the very confined space of a tent, if you had a Primus stove going full-on you'd fairly quickly get an asphixiating atmosphere. You had to watch that situation carefully. It's one of the great hazzards, because the first signs are of sleepiness, then a total stupidness, so that you don't know what's happening. And if you let it go, or if it should go unnoticed past the second stage then you're in a mess. Oh there were several accounts of that. One night Fred recalls he was on watch and he was in the main mess and one of the men, I can't remember which one, sort of rolled in the door and lay on the floor and started to mutter, ah, meaningless things and Fred quickly inferred that that was the problem, that the stove had blocked up in there and so he went down there and, saved their lives. (Didn't get a medal for that.) That was quite a hazzard, and an easy, and a frequent one.

Lisa

What sort of field work did you do and what sort of trips?

Jack

We, people like Fred and I, who had routinish jobs at the base, we only got on field trips by courtesy; we were sort of invited on them, or, they all, every field trip has a radio operator and I would sometimes go in that capacity, and Fred as a Met man (meterologist), not on any very long trips, so ... we were, both Fred and I scheduled to be on the major long trip of our year - the Prince Charles Mountains - but unfortunately the ghastly transport vehicles, the so-called Weasels, were so unrealiable that trip, after two preliminary forays, had to be cancelled and we were on the final trip, and I'd always wanted to see the Prince Charles Mountains very much, 'cause they're a very remarkable range. I never did it. So were were more or less incidentally on the field trips. In later years they had special traverse crews whose job was to do seismic soundings in the ice and all of that and they went very long distances and they had much superior vehicles. But, ah,we didn't.

Lisa

You've got a machine in the other room, a musical instrument that you explained to me had recorded sounds of notes, the recorded sounds of an actual piano.

Jack

When I hear what to me is a very attractive simple cadence of notes, I like to work out just what they are, and it depends on (pause), you don't hear them much in great orchestral music but you do a lot in keyboard music. And J. S. Bach is the outstanding example, and so in Scarletti of course, and in some way Handel. I just like to sort of work them out. That's all.

Lisa

Have you ever played an instrument?

Jack

N...Yes, I learnt the guitar, for a number of years. I wasn't very good, in fact I wasn't good at all. But it was fun and I loved the sound of it.

Lisa

Did you take that with you to Antarctica?

Jack

No, no. I hadn't learnt it then. I learnt it later.

Lisa

So when you were in Antarctica, did you have an interest in sound...

Jack

I had an interest in music, certainly, yes. But that was confined to gramophone records. We had a piano, which almost no-one played.

Lisa

I'm just wondering whether your interest in sounds, in that way, may have tuned you in more...to the sounds of the...

Jack

Ah, to a dregee, yes, to a degree, but, yeah, but then Fred had equal interest in music, more involved interest that I. He sang in a lot of choirs, and still does. But yeah, there'd be a connection. Yeah. I ...I think a tone deaf person wouldn't've noticed it at all.

Siobhan Davies, London, April 2008

Siobhan Davies, Endangered Species, 2006, Video installation

After participating in a dance workshop at her London studio, I spoke with choreographer Siobhan Davies. Siobhan had worked in the Arctic with scientists and other artists on a Cape Farewell expedition in 2005, led by David Buckland.

Lisa

Was your awareness of the changes that you experienced, perhaps witnessed, or certainly learnt about from scientists who were there ... did that knowledge enhance this feeling of interconnectedness that you expressed on Saturday [at the the Poison and Antidote forum at Whitechapel Gallery in London, 29th March], of ... no line between your body and the environment?

Siobhan

I don't think in all honesty I witnessed change. One, I didn't know what it looked like before. And two, I think I witnessed and experienced an extreme set of physical responses because I was in a dangerous situation. In other words, it is not central London. It is the high Arctic, which physically has an effect on you every second of the day.

So the knowledge is that I come back here, and I know I am being physically affected every second of the day. But now I'm more aware of it because I was put in that extreme situation up there.

Lisa

That's really interesting. So your experience there shifted your perception of here.

Siobhan

And it's also an emotional knowledge. So although the scientists were terrific, and I benefited enormously from simply experiencing other people's knowledge succinctly and intelligently put forward. That was just wonderful. In the end I think it was the emotional experience and knowledge which has been the greatest ... I was going to use the word fire, but somehow it's the wrong Arctic word for... an engine for a different kind of energy.

And then the experience of gradually understanding this lack of line between myself and where I exist, that's been ongoing as choreographic and dance artist(pauses)... research. I mean, It doesn't need to be research, because it's a fact. But funnily enough it's sometimes very ... you don't always work with the facts. You forget that it's a fact. So you have to go back and work with it, as a fact again.

Well in our society, from what I understand of what you talked about on Saturday, it's another one of those inconvenient truths.

Yes. Yes, you just, you forget that you are, that your mind and your body are made up of matter and that the place that you live in is made up of matter and that you are, each part of you is just moleculed, or remoleculed up into different ways. And by truly recognising that - not in a poetic sense, not in a ... any other sense than IT IS. There it is! It's what you have to deal with, what you have to understand. Because IT is understanding itself. Because it's a fact.

Lisa

So when you came back, was your value of dance as a way of us connecting with ourselves, with each other and with the environment, even further enhanced?

Siobhan

I don't know if I would use those words. (pauses, eye closed) ... This is going to be difficult for me to put in words. I don't necessarily think of myself as poetic. It's not that I BELIEVE in dance, although I do. It is that dance IS. And I hold onto that is-ness as a form of learning. So, as a form of learning I try to allow it ... I try to let it use me. And I was incredibly daunted that I should be asked to make a piece that would in any way be able to give an image, an understanding, a reason for engaging with climate change ... and I came up with something, and I was glad about it.

And if I could find something else to make, I would. But I don't want ... I'm also very aware that I don't think this is the time or place to overcrowd our imagination with things that could be unnecessary. In other words, I think in order ... that to find something, ideally you need to find something that would really work.

Lisa

I notice you have Tufte's book [Edward Tuffte, Envisioning Information] on the floor.

Siobhan

It's fantastic.

Lisa

It is. I've been referring to that and his other books. And I was very interested to hear you use the word accuracy in your talk, which is something I'm grappling with. How can art be accurate?

Siobhan

Yes, we're all, I think we're all grappling with that, and I'm not, you know I certainly wouldn't say I am accurate, but I think there is the pursuit of trying to find the right movement in the right time in the right place, or the right word and the right time and the right place ... is what we endeavour to do. And we miss, an enormous amount of time.

Lisa

What I find accurate, in [your art work] Endangered Species, is how it resonates with my own experience of the Antarctic, through very succinct use of line and sharp contrast between the black and the white, and so, just through the visual language, for me, it was an accurate representation of something I experienced, and from speaking with other artists who have been to the Antarctic, it resonates with their experience as well. But they've come up with different images ...

Siobhan

Were these dance artists?

Lisa

No. You're the first dance artist that I've met [to interview for this project], which is why I'm interested ...

Siobhan

So that's quite hard. I mean even the other artists on the boat were looking at me going, 'What the hell is she going to do?' Because most of us ... the movement that you could do was walk. And walking was tremendously enjoyable, partly because it took you out into this extraordinary landscape. And partly because it kept you warm. And (pauses) ... I don't think one felt as one with the landscape, but it did take you out into it, the act of walking. And the act of walking became incredibly important. And I was left with that when I came home.

Lisa

You talk about there being no division in the sense of no division between yourself and the landscape, and yet you say that in the Arctic you didn't feel at one. Did you feel it more at home here, when you returned?

Siobhan

I don't think, I mean I know we are one, (laughs) so, I know we are one, I mean I know this idea of matter. And the strength that that gives me is that (pauses)... oh gosh, this is so difficult ... That we have to constantly remind ourselves that we are not the dominant partner, the dominant ... (long pause)

Lisa

... force?

Siobhan

The dominant force. Good. But we ... it, it ... and yet at the same time, there we are, behaving as if we are, and achieving an enormous amount as a form of dominant force.

So our dominance is that we are achieving a change, in the climate.

So in one way we are a dominant force, but when it finally gets down to it, the planet will survive in some form and we won't. So at that moment we will realise that we have tipped the balance, and everything will have gone.

So psychologically, I suppose, and culturally, and politically, we are, and socially ... we are trying to deal with this the entire time, when we're making a mess of it.

So it's recognising that. And recognising that a lot of the time ... the reason I went out into the cold and was not at one with it is that I was extraordinarily aware that should any of my support team go, I would die out there. And it's that. So in one way you are at one with it, because you'd die in it, and that would be it. But all your psychological strengths would come to bear and go 'How am I going to survive this?'

Lisa

So our force, our energy as humans on the planet, has allowed us to go to the poles ...

Siobhan

It has.

Lisa

... in our ships, and in our amazing outfits, which separate us ...

Siobhan

Yes. But if we didn't have that separation we would ... I mean, I think what I'm saying is, that I recognise all the complexities. I'm sure I don't recognise all of them. I see myself within. I see myself warts and all. With all the problems that I have. I'm at least in the situation where I'm recognising the complexity. And there are no simple answers.

And in a mosaic-like way, artists will plant a seed, a work, out there. And that will magnetise a certain amount of people towards that image, towards that idea, towards that energy, which hopefully will feed them to become part of that increasing mosaic of people with energy, with ideas, with images, with solutions, with activities. And that's really what one's aiming for.

Lisa

Yes. And I think it [Endangered Species] has been very successful in that.

Siobhan

People question what art has got to do with it. Well, art is THE human activity. It is one of the things that separate us out, not made out of matter, but it does, so let's us use it.

I'm very conscious of the idea of propaganda, and with a lot of artists we've discussed many many conflicting ideas about it. As an artist, what is this idea that we're sending out? And that's where one uses the word accuracy. So you're shifting away from the idea of propaganda, because in its accuracy it becomes a proper thing in itself. And then if someone uses that energy because it has given them information about climate change, or anything else that you want to use your particular work for, then that's the thing, rather than you necessarily feeling you have to endeavour to find ... ah ... what is it ... a representation.

I imagine as an artist you're trying to make what I call the thing to have the IS-ness, to have the accuracy to stand on its own feet and then be used.

Lisa

When it achieves that point where it doesn't need you [its composer] any more.

Siobhan

Yes.

Lisa

It has a life of its own.

Siobhan

Yes. It has a life of its own and it is recognisable.

But you know I have spoken to Dan Harvey and Heather Ackroyd who are in the [Cape Farewell] film [on DVD], who I think are extraordinary artists and I think occasionally I've heard Heather say, 'Why not be a propagandist for this? This is so incredibly important. Let's not worry about words like that.' And I took on what they said. And at the same time you might have another artist who turns around and says, 'I think my work has to be what it is', and then within that, does have a particular kind of force, or idea. And then you speak to an author like Ian McEwan who I think would like, in one way, to to write something about climate change, but won't until he knows that the thing he's going to write is a real thing.

Lisa

Yes. I totally agree.

Siobhan

I'm sorry for all these 'Things' and 'Its' and 'Is-nesses', which are not brilliant use of language. And yet, it's very important for all of us not to become, not to be pretentious, not to feel smug, not to feel we have a knowledge that other people don't have. And, like Alex Hartley's piece, [it is important] to have intrigue and humour when generating an idea. That is really going to grab hold of more people.

Lisa

Exactly. Yes, it's connecting with people. I totally agree.

There is a perception that people who have been to the poles are some sort of secret society. So it's important to break that down.

Siobhan

Yes. I feel unbelievably privileged that I went there.

Lisa

One of the things that I find ... I can use the word accuracte ...in your work [Endangered Species] is its remarkable clarity of line. It seems to reflect a shared experience of the ice. It's just too sharp and too perfect, too pure. And you draw that visual language from the environment. And the other thing was the dark and the light. There are only two seasons at the poles. There's winter and summer. So people who know that would know that when they see your work, in your use of black and white. So many people use lots of colours. If you're only there for the summer it's all very beautiful but it's a little oceanic and there's nothing tangible or clear to grasp amongst the confusion of colours. So that's what works for me in your work. Yes, it's a personal response, but can I see the [human as a] species, and I think of Darwin ...

Siobhan

Yes.

Lisa

... and all that that [Dawinian theoory] brings. And then I see the ice, so it's grounded here (left arm extends) and there (right arm extends), and within the dancer, this human flesh and blood. And so it goes beyond the personal.

Siobhan

That's good. It was extraordinary going into the Natural History Museum. And again, I was slightly poleaxed about what to do. But when I was there I saw these extraordinary wooden specimen boxes. And within the specimen boxes were quite often a species that had gone. They mostly looked a bit mouldy. And I found that very moving. I found looking at the fossils, which are the imprints, and are very linear, very clear, calligraphic marks of a creature gone but left in stone. And I found that very focussing. And I found that idea of Victorian collection ... that we collect things, to observe. I don't know what else to say about that, but that idea of collecting to observe.

Lisa

Well it was an obsession, a Victorian obsession. People collected more stuff than they could make sense of. Which is why it's so beautiful that you've made this one piece, this one thing that looks like a part of a huge collection.

Siobhan

Yes. And it's only one. It's a nice way of putting it.

Lisa

It's your contribution to what Heather Ackroyd, and other artists are doing, to raise of awareness. That's how I see it.

Siobhan

Yes. Well I think it is. You just put your ... the idea that you think is the thing, the best thing that you can produce, and you put it out there. And I'm glad that it's had the response that it has. In the main I think it's had quite a good response.

Lisa

I was going to ask you, and I don't know if I need to now. But ... this is my last question. When I get back to Australia, I have a group of other artists and dance therapists and art therapists, who have agreed to work with me, in moving and drawing in response to some Antarctic texts.

Siobhan

Drawing will be very useful to you.

Lisa

Yes. I've done some preliminary work in that and I've found it very powerful. My question was, given your experience in the Arctic, and as a dancer, a teacher and a choreographer, are there any scores you might suggest?

Siobhan

I thought about that yesterday. Max Eastley, who was the composer who went up there, has all these sound scores. And you could probably get one of those even if you went to the Cape Farewell Office at the South Bank. Because Max was here yesterday.

Lisa

Sorry, I ... That's a musical score. I was thinking of a score for movement improvisation.

Siobhan

Oh, those kind of scores.

Lisa

But that's a brilliant idea that I hadn't thought of.

Siobhan

It's just that it's the sound of the Arctic.

Lisa

Beautiful. And I saw his sculpture, with the glass objects that represent the sound and appearance of ice [in the exhibition, The ship: the art of climate change, at the Natural History Museum, 2006].

Siobhan

Yes, that's it. And he's made a sort of whole Arctic symphony. An hour long.

Lisa

So if I go ...

Siobhan

Go to the Cape Farewell office.

I think it's quite good if you make your own score [for improvising responses]. I think text is always useful. I think maybe it's like a collection of things. If it's text and drawing, ... rhythm.

I think to keep to a particular rhythm ... this is choreographically, not anything to do with climate change ... to be clear about a rhythm is an incredibly good discipline. To be clear about certain timings gives you a structure and a discipline, so you don't wander off and make phrase after phrase after phrase after phrase. One phrase begins to erase out if you're not careful.

So, use your word accurate, give yourself a discipline. Say OK I'm going to do something for a certain amount of time. And make the time very short. And then do it a certain amount of time again on the score. So the score gives you timing, imaginative idea, geographic idea. And then, get on with it.

Lisa

That's brilliant!

Siobhan

Ha! (Laughs, claps hands) ... I'm sure you knew that. But I think we all know that, and sometimes we just need to be told again.

Lisa

And sometimes we just forget. It's very easy to lose ourselves in oceanic feelings.

Siobhan

Oh yes.

Buenos Aires, March 2008

Spanish artist, Parmen Pereira, at the Sur Polar exhibition and conference, Buenos Aires, Argentina, March 2008

I met Pamen Pereira at the exhibition and conference, Sur Polar, in Buenos Aires, in March 2008.

As we hung our work for exhibition, I became familiar with her work. When she made her conference presentation Pamen spoke in her native language, Spanish. She spoke some English, and so as we travelled by bus from the conference to our hotel, she explained what she had said in her presentation. But it was noisy on the bus which made it difficult to hear. Although an English transcript of her talk was available, I was interested to see the gestures that she used to describe her experience of Antarctica. Her expansive gestures reflected her feeling of connectivity between humans and the world that was heightened in Antarctica.

We sat cross-legged on the floor of the gallery as we spoke.

Lisa

I was hoping you might explain to me that experience that you described to me on the bus.

Pamen

Yes. When I arrived in Antarctica I was looking for ar - a solitary experience. I am a solitary person. When I arrived I must be with a lot of people - I didn't hope - expect? - this. One day I went up to climb the glacier and I did see a little refuggie - how do you say?

Lisa

Refuge?

Pamen

Refuge. Little house in the - refuggio, yes. Then I said, I want be here. This is that I want. And the people say, Oh no, you go to see someone. I said, Oh, no, I don't need - nothing - only I will want to work, I only stay here - what I see from the door is enough. And I convince the chief in the station - I can go to the glacier - for three days. Is the most great experience for me. The silence was there. I thought if I'm quiet I can hear the blood in my veins. The sound of the (mouthing) - saliva - the noise of the body was (breathes deeply in) - I can't explain really (long pause - enormous! Very big noise. The noise of the clothes (mouthes the sound of clothes against the body). Everything - remember the here and now. There is not another thing. The world is normal. Here, the world is struggling. The world is only one. Is no different - is the same thing - in Antarctica, in everywhere. But in Antarctica, is more easy to take a conscience of this.

Lisa

An awareness?

Pamen

Awareness?

Lisa

To feel it.

Pamen

To feel it?

Lisa

To feel the internal connected to the external?

Pamen

Si. The feelings interior and the sensations exterior, are one thing. No I am here (gesturing one place), and you are here (gesturing another place). In Antarctica is more easy to see. You see?

Lisa

I understand.

Pamen

(to) feel this ...

Lisa

Connection?

Pamen

This connection. yes. Because there are not interferences - distractions. I went to the station at the time when the people go to take me. I went to the station, and I must change my vision.

Lisa

Your purpose?

Pamen

Yes. In the station you're always with people. Always. For breakfast, for dinner, for lunch. For me is difficult - I am sociable. I like people. Is difficult for me to be always with people - little tension. However. I can feel another thing that - I got, a new experience, that I think was very important, for me - my concept about the life around the universe.

Sometimes one thing that you draw are yours. But I could feel that, this is No. No true. No. There are mental substances. Substances of mind, mental substances, that is the Big trouble, around (gesturing all around us).

Lisa

So outside us.

Pamen

Yes.

Lisa

Beyond you.

Pamen

Yes. The universe is a thing with no life - that can't think for itself. Life is here, in people.

Lisa

I'm seeing you wave your arms above your head, as if to describe the troubles that we feel are within us are actually out here.

Pamen

Yes.

Pamen

And this is what you said to me in the bus.

Pamen

Yes. Si.

Lisa

And then you said something about how we all connect to those.

Pamen

Yes.

Lisa

Each individual person.

Pamen

Yes.

Lisa

Connected ...

Yes.

Lisa

... to this trouble.

Pamen

Yes. Yes. Each person use little fragment, or little piece, of this huge, enormous substance of mind.

Lisa

You know C G Jung's idea of the universal conscious, that is beyond all of us, and we all have a connection with it.

Pamen

Si Si. Yes. Exactly that.

Lisa

And this is what you felt in Antarctica?

Pamen

Yes. When you come, you always think about something. But when you observe the situation, you can feel this is no your drawing. And it is possible to connect with people. Because only speak with words. People speak with heart, or with mind.

Lisa

Or with images, pictures ...

Pamen

Yes. Claro, claro.

Pamen

... or with music ...

Pamen

... with films.

Sydney, February 2008

Geoscientist, Jo Whittaker, was in the final stages of her PhD when we met at the University of Sydney. She agreed to describe her knowedge of Antarctica. Jo's research interests are in the field of plate tectonics, geophysics and geology specifically looking at the formation and evolution of continental margins and oceanic crust. She since completed her PhD from the University of Sydney in 2008 on the tectonic consequences of mid-ocean ridge formation, evolution and subduction.

Jo

(drawing legs up to sit cross-legged in her office chair) It's just so nice, when you're that tired, and you're warm and snug and you can see out the window, and all you can see is whiteness, and oh, you think, thank goodness I'm not out there, you know, it's really good to be in the warm, and people are bringing me tea and biscuits...it's really great.

Lisa

So do you think this has something to do with what people mean when they say it's a landscape of extremes?

Jo

I thinks so. It probably is, yeah. You have...because it can change so much. Like one day it can be beautiful and sunny, and you'll be having a great time and everything is relatively easy. And then you know, a few hours later you can be battling to make it 4 metres to go to the bathroom. Yes, it can change so much in quite a short space of time.

And it is so beautiful, but so harsh, and, if something goes wrong it can go wrong in a major way, and I guess you've always got that in the back of your mind,that it can flip really quickly. You don't have the support mechanisms that you would have normally, in daily city life.

Lisa

But you have each other.

Yeah, people have very intense experiences in Antarctica and form good groups of friends in a very short period of time. I still keep in contact with quite a few people I went down with, because you feel that you really know people, because you're all in there together, and you have to look after each other, you know, and you can't just wander off and hang out with some other people because there's no one you can do that with. You're stuck with the people you're with, and so yeah, you form these really strong bonds I think, which is really nice actually, and maybe something that's lacking from modern society.

Lisa

What were some of the challenges for you personally, living in such close quarters with other people?

Jo

I don't mind the close quarters. I like company. I actually found major challenges were not showering for three weeks. That was not very good. And I didn't really realise how bad it was until we got back in the Hagglands, you know the big warm vehicles, to drive all the way back to base on the last day, and you know, everyone warms up, and starts taking clothes off, and you kind of (drawing breath), take in deep breaths and you know, like "Oh dear, someone really smells, and you kind of get a bit closer to yourself and you're like, "Ooh, could be me actually!." (laughs)

Lisa

Do you think the sense of smell is heightened in that environment, because there are no, or very few other smells, unless you are close to a penguin colony for example?

Jo

Maybe. Maybe you notice the smells so much because when you're out on the ice you don't really notice that many smells because there aren't any.

Lisa

So what was the most enjoyable physical experience that you remember having?

Jo

I think riding along in the skidoos. It feels really liberating. You got this vast expanse, and you can't hear anybody else, you've got, you know, ear muffs on to keep you ears warm, and it's just you and the skidoo, out thee, and it's exhilarating, because you can go reasonably fast on those roads. But it's also very peaceful, because you're on your own, and you're sort of taking in the scenery and you're heading off, and specially when you're going out into the field areas you're going somewhere new, and you don't know what's ahead, and you lose that sense of space as well; it's very hard to tell the distance - you know, how far you're going, and how far the distances is between you and those mountains over there. You feel so free and open and just you, hanging out, in the centre of it all.

Lisa

So you had the experience of being together with people, and were enjoying that, but you (also) had the extreme opposite of that.

Jo

Yes, I had that on the boat as well I think, sitting on the top of the - what do they call it - the watch tower, the out-house, or whatever, at the top of the boat, and just sitting up there on my own, looking out, over, at all the icebergs, and all the ocean, and Mount Erebus, and having the same sort of feeling of being, well, just peaceful with yourself and looking, and taking in all the scenery and yet there were all these people, really close by, that you can hang out with. So, feeling secure, I guess, but also, yeah, I don't know, taking in the environment I guess.

Lisa

What was the thing that most excited you in terms of knowing Antarctica from the perspective of a scientist? Was there any surprise? Was there anything in the work that you did that suddenly came together for you? Or did you see what you were working on from another perspective perhaps?

Jo

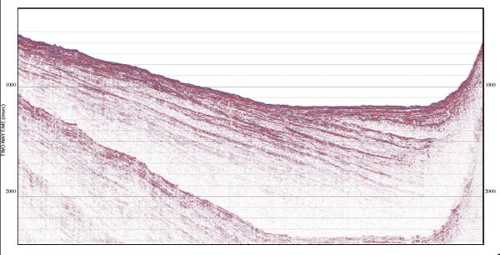

Definitely on the ship, when we got on, as a student, I had people explain to me how collecting the data, how collecting seismic and magnetics and that sort of stuff worked, theoretically, you know, shown on pictures, or diagrams or whatever, but it's not until you actually - it wasn't until I was actually on the boat, and saw the instruments go in the water, and the cable get reeled out, and actually see the air gun go off, that I actually understood how it was all working, and you know, exactly how everything was laid out, and it just sort of made it so much easier to understand how it work. And then that feeds into being able to understand what can go wrong, and why you might get certain anomalies, or problems with your data, because you can sort of visualise how it's all happening and what's going on, much much better I think...

Lisa

If you've been physically there.

Jo

If you've been physically there, and physically involved in putting out the equipment. You know what can go wrong. And it's the same on the ice. You know that sometimes ice is too actually hard, so you get the equipment in the ground, and you have to maybe drill a hole to try to get it in, a bit, and so you know certain things can go wrong, and maybe you've got signal loss in certain cases because of high wind, or really hard ground, or something like that. It just makes you sort of more associated with the data, or something. I guess it's not like getting data from someone else. I mean, now, I get a lot of data. It just turns up, as a file, and I use it, and that's great. But you don't know the ins and outs of the data, and what's happened to it, and also the lengths that some people have gone to to get it, because I think you forget, when you just get given data, that collecting data is sometimes really difficult, and really is a lot of work for what maybe looks like a small amount of data. But maybe, you know, but maybe that one piece of data that you take out can be a really crucial piece of a puzzle...(inaudible)...you never know what you're going to get!

Lisa

One of the purposes of my study is to help people connect with the Antarctic landscape, through the work of scientists, so I'm really interested to hear about the way you physically connected with the landscape in a way that gave more depth, if you like, to the data - your data in particular, and then by inference to other people's data, as it came in, since you had that experience - that appreciation, I suppose, of the human, physical connection with the landscape, that's necessary for collecting this kind of information.

Jo

I guess the scope of - I mean because you can talk about going to the ice caps, and how they affect - because I'm interested in sediment and how it accumulates - I mean you can talk about how ice caps and stuff move sediment around and can wane and flow and affect the amount of sediment that is deposited in the oceans nearby Antarctica - neighbouring seas. But you don't really get the scale of it, I guess maybe, until you get there? And maybe when you're flying in - because I flew in both times with the Kiwis - and flying in and seeing just - it just stretches for ever. You can really start to - maybe you can't really get an understanding of it - but at least you could at least start to get an understanding - of just how enormous it is. And if you have climactic changes, or just changes in the ice sheet - the distribution patterns or, climatically, its extent, you can understand that would have a big impact then on the sediments deposited just off-shore, because, you know, the advance and retreat of those glaciers and ice caps, yes it's just so big it really would have a big effect. And maybe you wouldn't appreciate that so much if you hadn't seen it, I think, maybe...

Lisa

...brought it tome human scale.

Jo

I think so. Yeah, you think, wow, this is such an enormous process, and it must have such major implications for what's going on and how everything fits together and explains what I'm seeing in these, you know, what are essentially xrays, of sediment underneath the sea floor that we collect.

Lisa

So listening to the sensors, or the explosions, and then reading the sensors, did you get a heightened sense of the age of the place, given that it take so much time for this ice shelf to build up, to be that thick? Did being there deepen your appreciation of the age of Antarctica?

Jo

I don't know about the age, but definitely of the hostility of the environment to getting, to collecting data, because where we were, the ice shelf sits on top of, actually, ocean, and the sea bed's underneath that, and so you have ice shelf, like 100 metres thick ice shelf, and then you've got the ocean and then you've got the sea bed, which is what we were trying to get at. And to get at that, it's really difficult because the ice shelf actually dampens the signal of your explosive, essentially, when you blow it up. It's supposed to go down, go through all the layers, go through the ice shelf, go through the water and into the sediments, and show you all the different layers of the sediment. You have to go through quite a lot of processing afterwards to try to get rid of the signal of the ice, to actually get to the data.

We weren't looking at data that was particularly old. We were trying to look at data, in that case, that was up to 5 million years old, in a channel round Mount Erebus.

Lisa

As opposed to 40 million years.

Jo

Yeah, that's right.

Lisa

Oh, nothing, that's nothing (both laugh)

Jo

Yeah, well, I mean you have to understand that the reconstructions that I've been doing, like in this paper (?), I looked at reconstructing Australia moving away from Antarctica between 80 and 50 million years (ago). So, yeah (laughing), I've got maybe a slightly warped perception of old and young.

Both - It's all relative.

Lisa

Now, I'm interested that you are doing two forms of study, like one is the rifting - or rafting?

Jo

Rifting, yes.

Lisa

...between the Australian and Antarctic continents.

Jo

Yes. Australia and Antarctic used to be connected.

Lisa

Yes.

Jo

Yep.

Lisa

...and the other is the roughness of the ocean floor. What's that about?

Jo

It's just happened that way. My thesis was a kind of hodge-podge of, It's not. I mean, all these things are connected, but it's kind of like I do one thing, and then I start doing something new, and there's this small connection, and I think, that's really interesting, and so, as you're supposed to do in a PhD, you sort of follow that through and it turns into this whole new topic that is kind of related, but maybe a bit of a side track to what you were doing before. And so these two are fairly different. I mean the main connecting feature there is the mid-ocean ridges. So the mid-ocean ridges are the way the new crust of the world, essentially, is formed. As two plates move apart you get up welling magma that solidifies when it reaches the surface and attaches itself to each plates as they move apart - in our case Australia and Antarctica. And depending on how fast the plates move apart or what direction, or what that underlying mantle is composed of - the differences in the composition - it can affect the roughness of the crust. It just effects how it solidifies and what it looks like, essentially.

Lisa

So it's a bit elastic for a while, is it, and is shaped by certain forces?

Jo

It's not really. It's just that it up wells at different rates and the crust, and the crust sort of fractures and moves at different rates. It's not really elastic so much as - if you've got a lot of material coming up, it solidifies in a much easier, uniform manner, whereas when it's slow, it tends to be episodic, so you'll get a burst of magma activity, and then nothing, and so then it sort of fractures and breaks up, and you get another bit and it tends to be much more jumbled and rougher.

Lisa

This obviously fascinated you enough to divert you.

Jo

The roughness stuff, the sea floor roughness stuff is really interesting actually. Don't know if you can see the map on the back there (both turn to look at a large map (framed) resting on the back wall of the office). You can see that the sea floor is really rough ...

Lisa

Yes!

Jo

... and not in a uniform way.

Lisa

No, things cross over.

Jo

Yeah, there's all kinds of interesting stuff going on, so there's obviously a few different parameters involved in creating those different forms.

Lisa

It's like looking up into the sky, and seeing the different levels of the clouds.

Jo

Yeah, yeah. Yeah, you're right.

Lisa

It's beautiful.

Jo

Yeah, there are some really quite nice images from the marine data sets.

Lisa

I'm interested in the fact that you did this work with the sensors on the sediment on an Antarctic ice shelf. Is that because you can't do it further north, where I would expect there to be more evidence of the rifting between the two continents to be. Is it just an ideal place for you to work with this equipment to get the sort of information that you're after?

Jo

So the two - those two scientific problems are somewhat different. For the rifting, we tend not to use seismics much. We tend to use magnetics and gravity, and it tends to be even further off-shore than what we did on the ice shelf. So you tend to use - or if you need to go south, to Antarctica - you use icebreakers. Most of the time you can just use normal vessels in the rest of the world. And whereas the seismics are for looking at the sediment. It was an entirely different project and we were interested in trying to look at climate in Antarctica and see if there has been - you know, what climate changes thee have been in the pas 5 million years, because getting a sediment record for Antarctica, of the recent past - the past 5 million years, is actually quite difficult, because you constantly got the ice sheets coming over, and any sediment that's deposited in a warm period can then just be eroded and removed by a subsequent cold period where the ice shelf goes up further. So you need to find a place where there's been subsidence. And because Mount Erebus is next to the Ross Sea, and (is) a whopping great volcano, it actually depresses the surface of the Earth, essentially, and makes a little gap just sort of in a ring around Erebus, where the recent sediment has collected as it's - as that crust has sort of sunk around Erebus. So it makes a very nice to collect that sort of data if you want the past 5 million years record.

Lisa

So it gathers, it gathers sediment, and is uninterrupted by the glacial actions.

Jo

Yeah. You could think of it, you know, when you stand on a trampoline, and you end up with that depression all around you. If it was all filling up with sand you'd get the oldest stuff at the bottom, then if someone hosed you down or something, you might lose that top layer, but the stuff underneath would remain, and you'd have quite a nice neat record there - essentially is the theory behind it. And it worked quite well, apparently, 'cause after I left Victoria University and they said everything worked out pretty well, 'cause we'd made some estimates about what age we thought things were going to be, from when I went on the boat, we made some estimates of ages of layers (of sediments) and apparently we weren't that too far out, so that was good. They drew on that later as part of ANDRILL - they drilled those sediments.

Lisa

What about an aesthetic experience of Antarctica. Did you, were there any particular moments that you enjoyed for their aesthetic value - the look and feel...

Jo

Sure, heaps I think (laughing). I think maybe that's a hard question to ask.

Lisa

Mmm

Jo

...'cause you can't really, it's hard to pull those apart, and separate out one particular moment that you really remember above all the rest of them. I mean I can think of lots of examples where you sit, and you're like, wow, this is, you know, this is amazing, looks beautiful. Am I allowed to say drinking beer back at Scott Base, and looking out the window, and watching the sun get closer to the horizon, and just feeling relaxed, and... yeah, it was beautiful.

Actually another time, on maybe on another emotional level: We were one of the last groups to leave Scott Base at the end of the season, just before wintering over, and they actually had a changing of the flag ceremony, where the old staff were leaving and the new staff were getting ready to winter over. And the three of us went to that changing over ceremony. And that was quite moving, because obviously it was the changing of the guard of the staff at the base, and they were quite emotional about it. And it was really nice to just be included in that. Because obviously we weren't staffers, or scientists down there. Yes, I remember that quite clearly. It was quite an interesting moment.

I've heard that before, that this changeover time is very emotional, and people can get quite upset.

Jo

It does seem that way. If people have wintered over there for 10 moths, or whatever it is, and sad to leave, and the new people may be fearful - nervous about what's going to happen over their winter coming up, and - I guess, and it's hard to let (go)...'cause I think, as we spoke about before, you make those really strong bonds. And it must be a hundred times more for the people who have wintered over and spent - you know, Scott Base has only 15 or something of them over the winter - so for them to break up and go home and enter normal life again must be quite difficult.

Lisa

And also, connecting with the place itself.

Jo

Mmm. You must become very attached to the place, yeah, over the winter.

Lisa

Did any of that happen for you, in your time there. I know you were there for, what, 6 weeks?

Jo

Yeah. Not really. Oh, 'don't know, I mean, I really enjoyed the closeness of the people, but I don't know if it was so much the place as the sense of community. I know that's brought about by place. And you only get that sense of community because of the isolation of where you are, and the conditions that you're in.

(note: Could we be talking about world's present condition - in crisis for future human survival?)

I didn't necessarily feel, you know, emotionally attached to the landscape, as more to the people, and sense of community I think.

Lisa

It's not a friendly landscape, is it?

Jo

Not particularly, but it's very beautiful. But maybe it's a bit like the Australian outback. It's very beautiful, but it's not really - you can't just ease into it, and take it for granted, can you?

Lisa

No.

Lisa

Did you get a sense at all about how your science fits in with other science programmes, when you were down there?

Jo

Yeah, it's really nice because you do have time to sit around and talk with other people, specially at the end of an expedition, and you're waiting to go home, and you're there for a few day and everyone's talking about how their trip went. And we ended up chatting to this biologist who was looking at fish, and all kinds of different people - diver, and people measuring ice crystals - and all kinds of strange things that I'd never thought of before.

But it seems a lot of the research down there is ultimately related to climate, or the effects of climate, so it's kind of interesting to see how people are approaching it from all different ways.

It's nice to think about science as this sort of organic body that's ultimately working towards one course, 'cause you get so caught up in your own little piece of it that everybody sort of does their bit and, yeah, and it all sort of accumulates, doesn't it? It's good, that, about science. I love it.

Lisa

Mmm Well I was an artist amongst scientists, and I - that was a real bonus to me, to be in on those sorts of conversations, and to just learn, and see other people learning. Everyone grew.

Jo

Yeah, you learn so much when you hang out with a whole lot of other scientists and artists, and all these people who are down there, because everyone knows something different, and has a slightly different perspective on how every thing's growing, and what's happening.

Lisa

How old were you when you went down?

Jo

I went down in 2004 and 2005 so I would have been 24 and 25.

Lisa

And do you think the experience changed you in some way?

Jo

Yeah, I think it really did. Yeah, I don't know if I could tell you a definite thing that it changed, but I certainly though more about community and what's important. It's really important for me to have a network, a close network of friends and I think that was em phased, and really recognised it in myself in Antarctica, and that was what I really really enjoyed about being down there. Yeah, maybe it helped me grow up and be a bit more mature. One can only hope! (both laugh)

Lisa

Thank you.

Jo

No problem Is that OK?

Lisa

Oh, yes. I'll give you a copy of that.

Jo

Ah, OK.

Lisa

Well, it might be interesting in the future.

Cambridge, March 2008

Unlike the meeting with Jack Ward, which came about by chance, the meeting with Dominic Hodgson was carefully planned. I Emailed the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) to ask if any scientists would be willing to be interviewed about their Antarctic observations and experiences.

Dominic replied, and arranged for us to meet in a quiet room in the BAS library. He seemed eager to share his knowledge of Antarctica. We used gestures and line drawings to explain and confirm understandings of scientific concepts. Because the drawings that Dominic made were mislaid after the interview, these have since been re-drawn.

Dominic introduced himself as 'part paleoecologist, part quaternary scientist'.

Dominic

It's like environmental archaeology, forensic science. We use a lot of similar tools and technologies, and we're trying to find out what the natural deposits can tell us about what the world was like in the past. It's like a history book in time.

I focus on the last 12,000 years, so it's not big in geological time scales. It's about 12,000 years, so it's focused mainly on the present interglacial period in which we're living now, so, our environment, our geological sort of heritage in terms of our interglacial situation, that's allowed our civilizations to develop as they are today. So it's important to focus on that part, because all the tiny variabilities in climate, just in this interglacial period, have led to rises and falls in entire civilizations. And these are just small little blips in the record.

And before that, you've got huge jumps, glacial-interglacial jumps, and those would have had massive effects on civilizations, and globally affected the successive humans in whole latitudinal belts, not just certain civilizations in Africa, or north America, or South America.

The big ice sheet of the northern hemisphere extended all the way down through north America, past the Great Lakes, and beyond. It extended down all of northern Europe, and it stopped roughly between the Severn River and the Thames. So, a huge ice sheet, kilometers thick, completely covered these landscapes. There were no humans living there. They were driven south into southern Europe in order to find enough food in order to survive. And that meant that the human population size was much restricted at that time because there simply weren't the resources.

And so, after those glaciers retreated, things started warming up, civilization spread out a bit, and they got more resources. It's only when you're over resourced that parts of the human population have got free time, and it's that free time in which you develop what we know as civilization, as opposed to being an animal that needs to find food. And when you've got that free time, that's when you get all the major great civilizations that we learn of in our school history lessons. All those civilizations are emerging, and that's because there's an abundance of a resource, either in your own territory, or because you've annexed someone else's territory to get it.

Lisa

I was going to say war.

Dominic

It's part of human nature. When resources are tight we have war and when resources are abundant we have war, just to get more. That's greed, isn't it.

Lisa

And survival.

Dominic

And survival. Well, I've tied the two together really.

Lisa

So before this present glacial period, we had these other very long periods?

Dominic

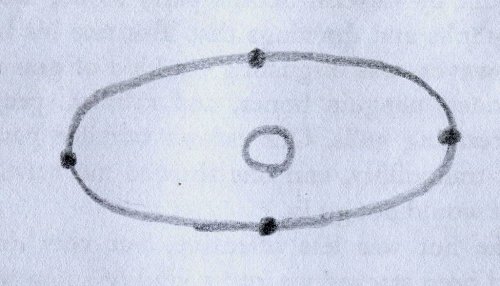

Yes. Typically, a whole glacial-interglacial cycle, in the last 400,000 years has taken about 100,000 years each. So there have been four of them. And then before that they were more frequent. They were every 40,000 years or so. And that's driven by variations in the way the Earth's and the sun's orbits interact. So sometimes, on 40,000 year cycles, there's a movement of the earth relative to the sun that means that the earth is actually nearer the sun and then further away, on 40,000 year periodicities, and so that drives the 40,000 year ice ages. And for the 1000,000 years, there's this thing called eccentricity, which is where the sun is moving in an ellipse, if you like, relative to the earth, rather than a circle, and so there are periods when it's further away and periods when it's closer to the sun, and that drives those glacial cycles.

Lisa

So the earth is moving around the sun in an elliptical orbit?

Dominic

Yes.

Lisa

You can draw a picture if you like.

Dominic (drawing with me)

The sun's in the centre of the solar system, or the way we sort of describe the solar system. And that's what the Earth does on a 100.000 year time scale. So here and here it's closer to the sun, and so that would be an interglacial. And here and here it's further away from the sun, so there's less energy, so the Earth freezes up, in a glacial period. So that's the eccentricity, the 100,000 year cycle.

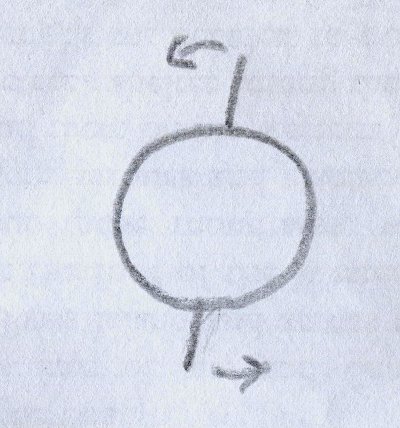

And then, you've got precession, which is a tilt of the earth.

Lisa

This movement(tilting sideways)?

Dominic

Yes. So instead of being upright and spinning on an axis that's steady, it actually moves from side to side like that (drawing) and you get a tilt.

And so you get points at which the northern hemisphere is closer to the sun, or further away. And that actually starts, triggers off glaciations. That's quite complex, because it triggers off glaciations by freezing up the ice across the Arctic and then once that happens, the world's ocean circulation changes, and that can trigger a glaciation in the Antarctic. But there are also theories saying that the Antarctic is driving the northern circulation initially, so it's a process that starts in one polar region and then transfers to the rest of the Earth.

Lisa

So both poles are part of the mechanism of change?

Dominic

Yes. They're linked because both of them have very important roles in ocean circulation. And so the Antarctic pushes out cold dense water into the rest of the world's oceans. In the Arctic, warm water is sinking down, and cold water is also upwelling. And so there's this complex interaction. But basically the earth is connected by the ocean conveyor. And if you cool down either pole it will have an influence on the opposite pole simply through that conveyor system. So that's why we study marine sediment, to get that element of the story out.

Lisa

The marine sediments?

Dominic

The marine sediments will record what ocean currents have been flowing in certain areas of the ocean, north or south, from grain orientation. But also you can tell whether they're warm or cold, from looking at the isotope composition of marine shells. So marine shells will form different ratios of carbon isotopes when they're in warm water as opposed to cold water. And you can study diatoms, the microscopic plants associated with different water masses. All sorts of little clues are available in the sediment record. You sort of assemble lots of these clues together until gradually lots of these lines of evidence will start agreeing. And then you know that's your most likely explanation of what's going on.

Lisa

So you'd be pretty close to the information that's persuading us that climate change is really happening?

Dominic

It is, yes, because the concentration of carbon dioxide is now higher than at any other time in the last 850,000 years. We know that absolutely for a fact because we can measure the trapped bubbles in the ice. And those trapped bubbles go back 850,000 years. There's an ice core called Dome C. You simply get those bubbles out. You measure the composition of the gasses in those bubbles. You measure how much C02 thee is. So we know that even with these massive swings in climate, between glacial and interglacial states, the C02 level has never gone beyond the level which it is today, that we've introduced into the atmosphere.

You can look at the glacial-interglacial cycles, but you can also look at methane and carbon dioxide. They're the two major greenhouse gasses, and how they naturally vary over glacial-interglacial cycles. And both of those are now beyond the range in which they would naturally occur in the last 850,000 years. And it's very difficult to conceive of any other explanation than our massive burning of fossil fuels being the cause of that rise in C02 in particular. You can measure the other sources. You know, there's C02 gasses from volcanoes in the ocean, and there are instruments all round the world measuring these things, and there's instruments in cities. There's a whole network of instruments. So all the measurements are being taken and it's the burning of fossil fuels which is the unusual component in this system, which hasn't been there before the first part of the 1800's, on this scale.

Lisa

What is unique about working in Antarctica?

Dominic

You've got really an open book. It also means you're more ignorant. You know much less. There's much less work gone before you. So you really sometimes are having to look at the landscape and try and read it for the first time in some ways, and figure out what was going on. And you get it wrong as well, so, you know, and there's ... we're all critical of each other, and gradually we progress through that criticism, and learn a little bit more each time.

Lisa

Is there was anything else you wanted to say?

Dominic

Well one of the things, when I saw your website, that struck me ... there were some comments on there of people actually being in the Antarctic environment and having these sort of experiences and feelings. And I have to say my first reaction was, when I arrive in the Antarctic environment, I never have that. I very rarely have time to sort of indulge in my sensibilities in a sense, because I'm involved in moderately complex drilling, and then I've got several tons worth of equipment, and thousands and thousands of parts. And going through my head, is usually, 'Have I remembered this? How am I going to approach this situation? What do the maps show us about the sea ice in this area in this time of year?' It's all about getting the job done in my head, and I guess the only sense I get of ... the only reaction I get to the landscape is usually that this is, this task we've set ourselves, is actually going to be a lot more difficult that we initially envisaged, because this landscape is, you know, these crevasses are big, you know, this ice shelf's difficult to cross, we can't land in an area we thought we were going to land in, and having to adapt because the landscape's forcing itself onto my pre-conceived plans.

Dominic

I probably get most reaction if I get time when I've finished, going home, or we've been delayed somewhere, you know, and I've finished my work. And that's a nice time to reflect.

Dominic

And when you look at your photographs when you come back. In many ways, that's the time when you really sort of appreciate what you've seen. And when you show your photographs to other people, and they're sort of blown away by some of the things that we've seen, and for me, you've sort of taken that in your stride as you go along. But to other people, it's really something quite extraordinary and remarkable. And you have to remember that, because it is a privileged job in a way. I mean you have to work hard to get it, and do it. But it is a privilege to work in the Antarctic. I'm lucky to have had so much of my career working in such a nice environment, and not spending 2 or 3 hours a day commuting and suffering in a city, which wouldn't suit me at all.

Lisa

Do you see Antarctica as a sort of symbol of hope for many, for the ability of humans to work together, and co-operate and share knowledge and work for a better future?

Dominic

I think in an idealistic way it's nice to hold onto it as that. Right now I feel that's under a lot of threat, more so than it has been. With the territorial claims being expanded in the Arctic at the moment, Russians putting down flags, Canadians extending their activity ... every one's trying to define their territory in the Arctic. And that activity's going on in the Antarctic just as much, but in a slightly more covert way under the shady auspices of the edges of the Antarctic Treaty. I'm pretty unhappy with some of the enforcement of environmental protection in the Antarctic. Basically, the committee for environmental protection in the Antarctic has limited powers to actually enforce anything. It just makes recommendations. So for example, in your own backyard, in the Larseman Hills, the Indians are about to build a base. They've got plans to build a base on a completely pristine peninsular.

There aren't that many parts of Antarctica left that are ice free, without human impacts. And I think we really have to treat those larger ice free areas very seriously in terms of their future protection. And I don't personally think we're doing a very good job at that at the moment.

So I think for some people it is a place used as an example for great international co-operation. And the Antarctic Treaty is operating as that. But it's a very very B-team treaty. It's completely over-ruled by trade agreements, agreements for military use. Countries aren't going to disagree with each other on an Antarctic Treaty matter if it's going to influence other areas of their politics that they perceive to be more important. It works at the moment because the issues are relatively minor. As soon as the issues become major, then I think it will be under real threat, I'm afraid to say.

It's the perverse thing, you know, if you take the Arctic as an example, the Arctic ice is melting, and so oil companies and mineral companies are scrabbling to gain access to new areas that are de-glaciating and that are now accessible for the first time. So we're going to burn more carbon, because we're going to dig up more coal. And that will make the problem worse. But for them it makes the problem better. They've got new reserves opening to them. So it's a sort of perverse thing, and although the Antarctic margins aren't de glaciating to the extent that huge new mineral deposits are becoming exposed, you know, on a sort of yearly basis, it's inevitable that the oil reserves there, and some of the mineral reserves there, will be seen as being exploitable within the next decades. And then there will be an intensification of our interest in the Antarctic I think. Which is a shame. But that's the way I think it will go unfortunately. Unless we're really robust about enforcing this vision of a world park, or a place for peace and science which is what it's banners have been in the past. Hopefully that's how it will stay.

Hobart, January 2009

Marine scientist, Steve Nicol, is Program Leader of Antarctic Marine Living Resources at the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) in Kingston, Tasmania. We first met at the Imagining Antarctica conference, in 2008, where he presented his paper, From Beautiful Creatures to Particles - How Scientific Terminology and Methodology Significantly Affects our Perception of Marine Animals (University of Tasmania, 2008);(Nicol, 2008). During his presentation he told a story about how his view of krill changed for ever after seeing one in its native environment.

In his office in Tasmania, he retold this story. Tapping his hand on his desk as he spoke seemed to emphasize it's significance. Rhythmic qualities in his gestures and voice suggested ways to use animation to combine his knowledge of how krill relate to their environment, and his subjective response to these 'beautiful creatures'.

Steve's story is set in the Bay of Fundy, Canada, where he went out in a small boat with a local fisherman to observe krill.

I remember that first day we went out. It was a mirror calm day, and you could detect where the swarms of krill were by where the birds were landing on the water. So we followed the birds. You could see the water changing texture as the swarms of krill touched the surface. Occasionally they jumped out, and, as they swam around with their antennae on the surface, they caused their own little ripples in the water.