Connectivity: moving, drawing, animating

The animation, Connectivity, was composed with drawings and words by four artists who have not been to Antarctica. I was interested to find out how other people imagined Antarctica to be, and if I could animate some connection between their imaginings and my remembered sense of it. Improvising with gestures, drawings and words were ways to engage in dialogue with other people to see what thoughts and feelings might arise. I wanted to know how an animation could be made to reflect some understandings arising from our dialogue. I wanted to make an animation that would capture some of the interactions that had occurred between people engaging with Antarctica, through imagination and memory. I wanted to do this because it is important to find ways to connect with Antarctica, which has so much to tell us about climate change.

Christine McMillan, John Smith, Kim Holten and Yoris Everearts are four Sydney based artists who had agreed to help me with my explorations. All had expressed a great interest in Antarctica, so I assumed they all knew something about it. When we met in a cold basement room with a hard concrete floor, Yoris immediately remarked how it was like being in Antarctica. We all agreed. So we know Antarctica is icy, cold and hard. What else? We sat in a circle and I gave each person a soft lead pencil, some sheets of white paper and small board to lean the paper on. I asked them to put down the words or pictures or both, that came immediately to mind when they thought about Antarctica. I asked them to do this quickly, without talking with each other or looking at each other’s work. This seemed to be difficult for some, as I watched them gaze off in the distance for a while before putting pencil to paper. Others began straight away. The words that emerged within three minutes were:

space, hostile, beauty, relationships, melting, lacking man made culture [Christine]; collage of impressions entirely through the media and 2nd or 3rd hand, desolation, strange feelings that arise when you are out of the mainstream [John]; timeless cellular memories, layers of history, parallels oral traditions, needs deeper understanding [Kim]; frozen memory, body, matter, purity – white [Yoris].

I recognised in all these words the Antarctica I had experienced. Specially interesting was John’s ‘collage of impressions entirely through the media and 2nd or 3rd hand’. So much of what I know about Antarctica comes to me that way. Antarctica is huge, and even if you have been there, you depend on the media to get an idea of its other landscapes you will most likely never visit. Or you can listen to what people will tell you about places they have known there. The Antarctic Peninsular, for example, is more in the media than East Antarctica, where I went. Australian expeditioners often call this West end the ‘pretty end’, in contrast to our more austere East ‘working end.’ Extending further north into warmer latitudes, the Antarctic peninsular contains more wildlife, and more rock protrudes through its melting ice. It is more colourful and alive in its physical expression of global warming. From the picture post card photos it looks beautiful and fragile. Satellite photos taken in recent years reveal to the world the dramatic collapse of the great Larson Ice Shelf. Methane escaping from other parts of the peninsular through rapidly melting ice is a phenomenon I can most clearly grasp through an artist’s visual response. Images of Andrea Juan’s Antarctic installation, Methane can be seen on the artist’s website. They dramatise toxic human impact on our planet’s fragile atmosphere, with swathes of floating coloured tulle representing leaking chemicals. When I first saw this image I was moved to find out more about the science that inspired her work. I found the transcript of a conversation she had with the scientist, Rudolfo del Valle, as they traveled towards Antarctica. He explained to her that:

Through the increase of the greenhouse gas effect gases, we are causing the temperature to rise too much and just in the middle of a rising cycle – this might break the cycle. I believe this additive interference is already dangerous. Nature might be unable to restore the balance.

This is the kind of dialogue an artist can engage in with a scientist that can shape her response to the Antarctic landscape. Her response will also be shaped by how she is predisposed, and the sort of materials and methods she has available to her.

Fig.01 Andrea Juan, Methane. Antarctic performance, Jubany, Argentine Antarctica 2005.

In the cold basement room in Sydney I was in dialogue with four other artists about Antarctica.

In all the words they wrote I recognised much of my Antarctic experience. Many expressed what the landscape lacks. Christine wrote that Antarctica is ‘lacking man made culture.’ By ‘culture’ she meant a long period of human history that shapes a place. Her word ‘space’ suggests to me a lack of features we can see, features that we would expect to find in more familiar landscapes. I read this as meaning the external physical landscapes one can know, the physical places you can walk through, as well as the internal landscapes that are shaped within our selves through feeling responses to our external world. The word ‘hostile’ suggests an extreme lack of emotional warmth, and even anger, expressing itself in the landscape against humans.

Some people grouped words in ways that suggest some contradictory feelings. I can read Christine’s words ‘melting’ and ‘relationships’, for example, to mean the opposite of her words ‘hostile’ and ‘lacking man made culture.’ ‘Warmth’ could reflect the intensely tender human connections that people can make with each other living in close proximity to each other in a dangerous place, and ‘melting’ could mean an emotional surrendering or release. I am aware as I write that I can find my own sense of Antarctica in other people’s responses. Such is the nature of dialogue, where meanings evolve through the listening and responding. Responding to these words I can feel my love for Antarctica with simultaneous fear.

Kim and Yoris wrote that Antarctica has ‘memories’ that are ‘cellular’ and ‘frozen’. Their words suggest that Antarctica is a sentient, feeling organism, where the ice knows its own past and ‘needs deeper understanding’. Their words accord with the Gaia theory of the Earth as a living being, the theory also reflected in the words of Antarctic scientist, Bill Burch:

…it’s the ancient air bubbles trapped in the ice which allow us to chart Gaia’s atmosphere going back millions of years.

Some of the artists drew images alongside their words. Some wrote their words like pictures. These offered visual clues about they knew the landscape. Christine’s marks in both her symbol and her writing reveal a layering of lines that echo Kim’s phrase, ‘layers of history.’ Both were drawing in response to an imagined landscape, and in their different ways arrived at a similar sense of it. I was interested and surprised to find such strong correlations emerging between the responses of two people who had never met each other before. And I had not worked with Kim before this session.

Christine said she drew the words as images, to reflect heir meanings. The ‘s’ of ‘space’, for instance, suggests dept beyond the page. She said she was mindful of the use of capital and lower case letters, and the different force each can have. The capital ‘H’, for example, gives an edge to the meaning of the word ‘hostile’.

Fig.02-03 Christine McMillan 2008

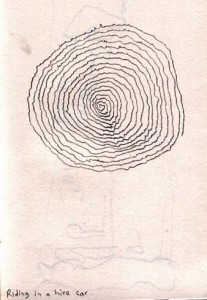

Kim drew a coil, which she described as representing things connecting. This in turn echoed Christine’s word, ‘relationships’, which she explained as the relationships you would have with people in Antarctica that might be very hard in such an environment. She said it also meant the relationship you would have with the buildings and the land around you. Her star-shaped form represented, she said, being connected with everything beyond Antarctica – how Antarctica is inked to us.

Fig.04 Kim Holten 2008

After listening to each of these responses, I led the group through a physical warm-up to an Arctic soundscape by Max Eastley . I introduced the sound simply as a ship moving through Polar ice. We moved as a group to raise awareness of our bodies, the space we were in, and the other people sharing that space. With eyes closed we stood still, and then gradually explored ways we could feel our weight through the floor. We pushed our weight down through bended knees, and imagined, rising from that bend, the top of our head reaching high above us. And then, with eyes opening, we played with feeling through our arms and torso the line of the horizon, extending our gaze outwards into the room. We moved towards and away from the limits of the room, and each other. We played with straight and curving floor patterns. This was a typical example of a score for movement improvisation.

A movement score is a set of limits imposed for performing improvisation within which to explore the use of space, time and energy. It provides a neutral structure within which dancers can attach their own meanings. Meanings can express themselves in any way through the moving, for example as stories, emotional states, and ideas. No emotional state is prescribed. A score is typically made up of a very few simple instructions. For example, to improvise for 50 percent of the time with large gestures and 50 percent of the time with small ones. The meanings that can arise from working within such a score can range between strong expressions of personal emotion and cooler, more formal abstract patterning of the body in space. This is a way of working I had learned from Joanna Exiner and Al Wunder in Melbourne. The sources of their teaching reach back to the work of Rudolph Laban, who developed a lexicon of human movement for movement performance and analysis. His approach has been integrated into a range of arts practices including theatrical performance, performance art, film and arts therapy. I have adapted the idea of movement scores for drawing and animating.

After moving, I asked everyone to draw from this experience, with their pencils on the paper. Again, I asked them to do this on their own. This time I observed no hesitation by anyone to immediately do this. The drawings seemed to come more easily after moving. Most people did several drawings on many sheets of paper.

Christine said she enjoyed exploring the variations in pressure she found possible with the pencil, which reflected her whole body exploration of her weight through her feet unto the floor as she moved. She told me later that when drawing this she had remembered another session we had weeks before, where I had suggested exploring this idea. She also wanted to draw differently than she had initially in the session, to break away from those patterns, to explore other possibilities. One of the reasons that improvising with a score can be effective in revealing feelings is that it encourages different ways of doing things. When shifting from habitual ways of physically moving, unpremeditated responses can be revealed. The lines, said Christine, recalled an earlier line quality reflecting the feel of ice, but in this instance they also reflected her awareness of the immediate physical space. There were open slots in the ceiling through into the room above us, where there was some renovation work happening. It was a most surprising and unexpected visual intrusion. These long slots of light above caught her eye and influenced her moving, which in turn became embodied in these drawn lines. This is the kind of unexpected connection that can happen in the moment of improvising, where immediate sensory awareness can be embodied in a dance and joined with other past memories. The net effect is a sensitivity of line and tone that conveys to me a sense of careful deliberation and sensory response. The lines have a delicacy about them and are at the same time describing a strong physical aspect of the room’s architecture.

Fig.05 Christine McMillan

John described his drawing as the curved and straight pathways he moved along the floor. Thinking back to watching him move I recognised the lines immediately, in their shifts between long and short lines of motion, and the smaller looping turns he made when changing direction. John had used various body parts to lead himself through space. This drawing looked like some kind of figure, schematically represented like some ancient totem.

Fig.06 John Smith

Yoris drew several drawings on several pieces of paper. His lines reflected the discrete structures gestures in his dance. I had observed pauses between gestures that are suggested here through the lines being separate, each with the start and end point, like the gestures he had made. I saw a sculptural quality in them. I imagined them, like John’s forms, as totems.

Fig.07 Yoris Everaerts

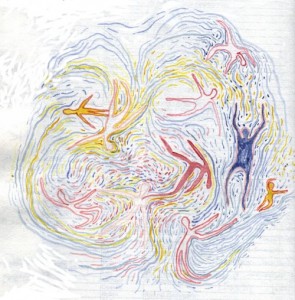

Working on just one sheet of paper, Kim drew how she moved beneath her initial words and symbols. She also added more words that connected with her experience: connectedness, unison, fusion, oneness, layers, space, wax/wane, levels, heart, breath. The drawings reflect her physical explorations around the room, moving through straight and curving pathways along the floor, and moving her body upwards and downwards. There seems a sense in the bottom left hand drawing of her awareness of the spaces between herself and others. Then in the bottom right, a more physical connection that she made with others is reflected. Kim had not done this kind of work before and was excited by her results. Her drawings were diverse, showing the different ways she had interpreted the movement score.

Fig.08 Kim Holten

In composing the animation, Connectivity, I improvised. This means I began working from a position of not knowing what the final outcome would be, in the same spirit in which the words and drawings that I was working with were composed. I approached making the animation as I would an improvised dance. It would be a discrete gestural response to some dialogues that happened between a group of people about Antarctica. I was curios to know what feelings might emerge for myself about my memory of it.

Animation is a much slower process than improvising through moving. It is important to work as quickly as possible in its initial construction, not to question what ideas come to mind, and to stick to the dominant idea once it suggests itself. Once an idea emerges that seems to make some sense, hours can be involved in tweaking. The challenge is to maintain the freshness of the creative moment, to accept the idea however simple it may seem, and to enjoy and fine tune all the nuances of interpretation that can be discerned.

I first of all selected words and drawings that seemed to connect. I then animated each one to simulate something of how they were originally drawn and written, tracing over the marks each artist had made. I varied the speed of the animated marks to suggest the varying rhythms involved in the act of moving pencil on paper. I traced the marks as closely as possible, yet in the tracing I was aware of imbuing them with my own gestural qualities, my own feeling responses. My own readings of their marks suggested themselves readily. For example, I emphasized the totemic quality I had previously found in John’s drawing by overlaying it upon itself, so it became a symmetrical form. I was aware, when moving John’s words, ‘strange feelings’, below the totem, that the downwards motion suggested that these ideas were somehow beneath a level of conscious knowing. This I understand to reflect my own position, in starting the exploration, working from a place of not knowing how the connections would emerge. The image fades away, only to return again to be re-read with Kim’s words, ‘cellular memories.’ I was interested to see how the meaning of the totem might change. Now I could read the totem as a sentient being, comprised of cells that could each remember. Have drawn the original shape over itself in reverse had created a whole network of internal shapes that suggested a cellular structure. Visually and through attaching the new word to the image, I had drawn connections that were not necessarily visible before. The totem, then could mean different things. It was the different meanings that that could be read into the drawing that interested me. The idea of the totem as a physical form with a cellular structure was just fleeting suggested. A sense of its material physicality was subverted by moving the whole form through space. It was like moving the drawing off the page. The totem remains two dimensional, representing an idea that is free to find connections with other ideas. The way the totem angles through the space and fades away is mirrored by the gesture of an incoming cellular form that Kim drew. The two forms move with seeming awareness of each other. The cellular form then falls downwards, to join the idea of an unconscious memory beneath, suggested earlier. I layered over this the animated lines by Christine, drawing the eye still further down. Layers of different people’s personal memories and ideas are drawn down together into some unseen place. Animating the words ‘connectedness’, followed by ‘relationships’ suggests that even though these layers are invisible, they are connected. The more discrete, sculptural forms of Yoris then draw themselves in, with the coiling extension of one form then connecting with Kim’s coiled ‘connecting’ form. This section is a small gesturing between Kim’s cellular form, Yoris’s sculptural forms and his word ‘matter.’ As the ‘matter’ descends I am thinking of our material destiny, depositing our cellular forms as sediments that may one day compress, form coal, and power some future human forms. The ending suggests itself through Kim’s word, ‘breath’, that leads to bringing her connecting coil upwards with that word. I find a meaning here, as the rising breath connecting us with Antarctica and everywhere else: we share the one world atmosphere. The animation took took three days to complete. The sound, by Max Eastley, was added afterwards. I was interested in the idea of the give and take of the dialogue I was having with the drawings, through animating, setting the rhythm of the piece. The sound worked well with what eventuated, and tied it nicely back to the memory of being together in the room, moving to it.

What was the value of this work?

A dialogue occurred between some artists reflecting on Antarctica. The completed animation reflects something of the tenderness and delicacy of interactions I observed happening between the participants and the landscape they imagined, through their moving and drawing. It reflects, too, a certain tentativeness we seemed to share about entering into unknown territory, embarking on this experiment in a space new to all of us. Then through a gradual unfolding of ideas connecting, I found a resolution, through ‘breath’, and a shift in feeling came through a change in direction, uplifting. Moving together, we demonstrated that a flow of thoughts and feelings about Antarctica could find form, through gestures to words and images. Working on the animation, I demonstrated to myself that this was a way to further dialogues I have with people, and in doing so, identify my own voice. I had been interested to see if this was possible, working only with their material. And yet not including my words and drawings actually made that easier. It was easy to see what was mine: the choreography of lines, and timing, the spatial design and sequencing. But most significantly, the passage of thought from tentative to resolution. There was great personal value for me, then, in this process of animating. Like dancing, it helped release flow of my own thoughts and feelings.

There is value for the participants in this way of working. The improvisation process, and the final animation reflecting that, offer glimpses into some thoughts and feelings that were shared. Participants can contemplate and follow up with their own inquiries. They may further question, for example, what ‘frozen’ and ‘cellular’ memories mean to them. Weeks after this session, for example, Kim said she had been moved from this work to work further with the idea of cellular memories in her print making practice, to explore issues of identity. Reflecting on the various aesthetic qualities of the drawings, words and movements, connections can be made with other memories and experiences that may be difficult to verbalize otherwise. As an arts therapist and sculptor, Yoris Everaerts has commented on the value of this work for releasing feelings, and opening up creative possibilities for expressing those.

The value of this animation for the general viewer is that it reveals the interconnections that were found between a particular group of people sharing their thoughts and feelings about Antarctica. It makes those visible. It shows how some people are responding. It has the potential to connect others with Antarctica in a similar way that I did through the work of Andrea Juan. It offers another point through which viewers can be led to know more about what Antarctica is telling us about our selves, and our impacts on the planet.

Like Andrea Juan, I have also talked with scientists. This animation is one of several I am developing to build a chorus of voices responding to Antarctica and its texts, reflecting dialogues I have had with artists and scientists I have. Some of these animated responses can be seen by anyone on my website, antarcticanimation.com. Improvised within the limits of what is possible for on-line animation presentation, these are brief gestures that reflect the kinds of dialogues I have engaged in, with other artists and expeditioners, and with the Antarctic landscape itself as I remember experiencing it in 2002. I am further improvising within a score suggested to me by a scientist Dominic Hodgson, who I spoke with at the British Antarctic Survey this year – the patterns of the natural motions of the Earth around the sun, known as the Milankovtich cycles. These interacting patterns cause the natural swings between Earth’s glacial and interglacial periods. Dominic Hodgson explained that human actions are tipping the balance of these natural cycles. From studying ice cores and sea floor sediments we know that levels of C02 and methane now in the atmosphere are unprecedented in the history of our planet. We do not exactly know what will happen, or when. That many of us do not know how to feel about this fact is not surprising. I am animating feelings some are sharing from a position of not knowing, as a point through which we can come to know what we can about the climate we are changing.